Many commentators are theorising about the impact of the post-Covid world on our cities, towns and other urban spaces. Will our previously busy city centres ever be the same again? Has the virus tamed our enthusiasm to get together, connect and collaborate?

The answer, I believe, is yes to the first and not by much the second. Human ambition to connect and exchange ideas, goods and services in person will continue. However, the risk to our health will now be part of the decision as to whether you do it.

One of the outcomes of Covid has been the changes to our high streets and urban centres. As bastions of economic activity, they have been severely compromised. As places to live and play, they are showing that change is required.

In the future, it is likely that places offering an experience to enjoy are going to thrive versus those places that are simply a place to work. Some of the commuter towns now realise that their geography in terms of local environment and ease of access to the surrounding countryside is just as critical as the ease of access to the train station and the motorway.

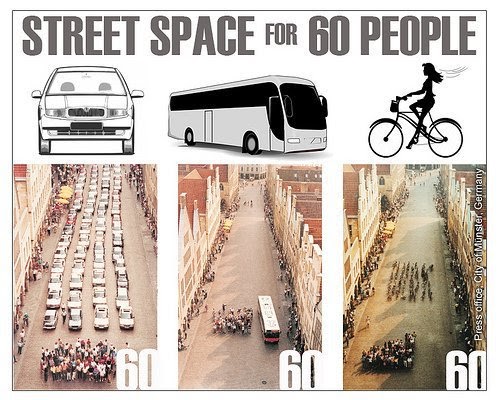

Why is it that despite the evidence to the contrary cars are still king? Is a car incompatible with delivering an improved experience? Assuming of course that the ‘experience’ of a place is what we are looking to deliver.

Tackling the “car is king” mantra is always going to be tough. The reality is that cars are great. They are safe for the transport provider that gets you door-to-door with relative ease and comfort. If you drive an EV they are non-polluting (at least at the point of consumption) too.

But the car has some downsides. Cars are resource-intensive. They are more complicated than ever (lines of code and processors required are growing). This article from Frederic Filloux “Code, on wheels” https://mondaynote.com/code-on-wheels-a4715926b2a2 – is a good explainer as to what is happening here and why. Cars (irrespective of powertrain), are not exactly space savers when it comes to moving people.

As we move into a world dominated by EVs; they too require a parking space. It will demand re-charging capacity (therefore, it will be static, space-occupying and connected to a charging source). The EV is still not solving the congestion challenge.

Also, the fixation on autonomous vehicles as solving some of the externalities of cars is going to take a long while to be realised. For it to be a success at a scale that will make significant impacts on our society and how we organise and approach life will take even longer. This is no silver bullet.

Cars are great for delivering us to these urban centres. However, we need to get better at moving around our urban spaces. This should encourage more walking, cycling, eScooters and shared environmentally friendly taxis (e.g. peddle-powered e-rickshaws). One way of facilitating this conversation is increasing awareness of the 15-minute place. The Academy of Urbanism hosted a symposium in September 2020 discussing this single topic.

Yet let us not forget that cars need to be catered for. So whilst at the same time as investing in safe walking & cycling infrastructure; it is essential to invest in improved parking provision, but not where it blights the economic activity (e.g. freeing up road space for cafe tables); above all though, we need better information. Information to tell drivers where to park and to give them the confidence they can complete that last segment of the journey on foot, bike, scooter or other shared mobility modes.

That means, for now, we are stuck with cars. They need to be included in the solution and not brushed under the carpet.

Going HyperLocal

A recent Mckinsey report (Five COVID-19 aftershocks reshaping mobility’s future – https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/five-covid-19-aftershocks-reshaping-mobilitys-future#) highlighted one aspect that requires further consideration. Hyperlocal information.

“The pandemic could also become a catalyst for more changes, as cities pursue their own, largely uncoordinated agendas. As a result, mobility players will need to develop a regional and hyperlocal perspective on this emerging mobility patchwork, recalibrating their market radar to anticipate these developments early on.”

What does this actually mean? For me it is all about understanding that for your place the best way to get there and to move around is made up of mode X & Y. Of course, for other people it may be modes X & Z. For others, it could simply be X.

So if cars are X, Trams are Y and eScooters are Z we can better provide mobility options that are fit for a place. Not every place will have the same provisions. Yet, all places should have great, freely available trusted information on what is available, where and when.

This requires investment in open data collection, processing and placement for 3rd parties to subscribe to. Along with some flexible measures on outcomes and thresholds for determining when a certain level of activity indicates stress in the system and place. For instance when congestion occurs.

The next aspect of producing the open data is then having a say in the outcome that wants to be achieved. Recognising that the circumstances and outcome change through the seasons (summer warmth versus winter snow), and events (weekend festivals versus a month-long Christmas fair). Having an ongoing and iterative community-focused conversation on the evidence is just as important as creating and publishing hyperlocal data on the status of mobility.

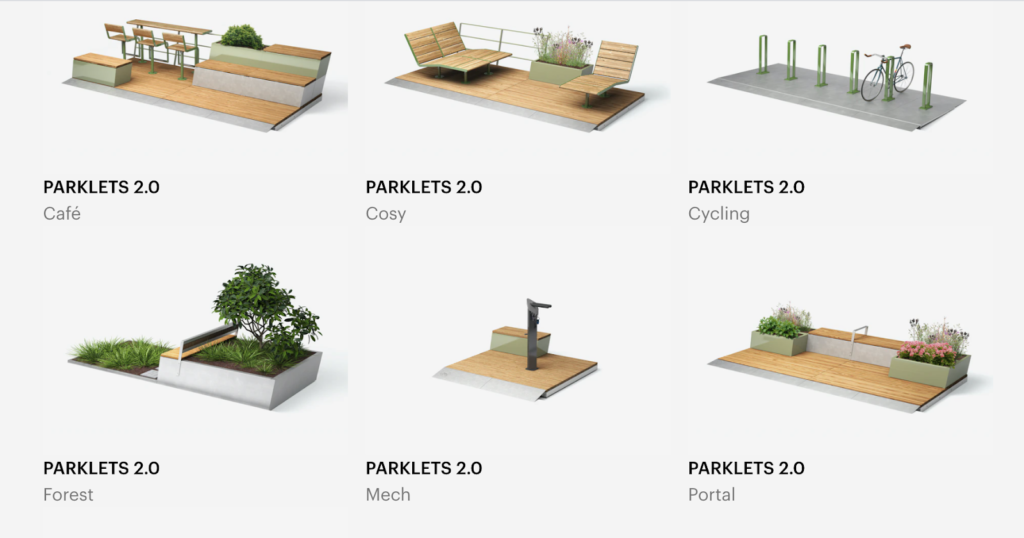

Alternative use for Parking spaces. Parklets.

Another element to consider is the true economic cost of a parking space. Is this really captured in the price you pay? On-street parking where that parking space could be a set of tables for a cafe. The parking space generates a small fee per hour. A cafe table generates 10x that fee per hour. Which also employs people, and delivers an improved experience for the patron. When in a cluster (such as a parklet set up) the overall economic activity of a place massively increases too.

See the evidence of the positive impacts Parklets have had in this article in the Conversation. https://theconversation.com/4-ways-our-streets-can-rescue-restaurants-bars-and-cafes-after-coronavirus-139302

“A recent parklet study in Perth (W. Australia), found a 20-35% increase in local footfall, and 89% community support.”

So why is it that retailers and communities are not convinced that reducing access to cars is a good thing? It probably comes down to where you are going, what you want to do and whether the offload of a low-traffic neighbourhood leads to more congestion and lower air quality. This article from the Guardian sheds some light on this debate: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/sep/20/the-new-road-rage-bitter-rows-break-out-over-uks-low-traffic-neighbourhoods

However, the overall message is that it is important to take people with you. Perhaps by using compensation for losing a parking space by offering free inner-urban public transport. Incentivise urban dwellers to reduce car use or even drop car ownership by embracing car clubs. This reduces parking demand and makes the vehicle asset more productive as it is in constant use and not parked up.

Places need to experiment and be prepared to fail when outcomes are not met or do not meet expectations. Places need to drive evidence and have open discussions about the outcomes that place wants to see. To do this places need to engage citizens and they need to listen and still be bold in their actions.

In short, places need to humanize.

Call to Action

If your place wants to create open data; identify outcomes and discover how to become smarter then get in touch at contact@kn-i.com